Fireflies of Ontario and How to Help Them Shine

On summer evenings in Hamilton, Ontario, the landscape flickers to life with soft pulses of gold, a glowing language spoken by fireflies. These beetles of the Lampyridae family don’t just dazzle; they support local ecosystems, control pests, and signal the health of our natural spaces. Yet behind this midsummer magic lies a fragile lifecycle, increasingly threatened by modern living.

If we want the glow to last, we must understand and protect what’s happening just beneath our feet.

Know Your Locals: Firefly Species in Ontario

Ontario is home to at least 23 firefly species, with many concentrated in the province's southern regions, including Hamilton.

Lucidota atra

The “dark firefly.” While part of the Lampyridae family, this day-active species doesn’t produce light. Its role in the ecosystem remains important all the same.

(Photographed in a Hamilton garden.)

Some of the most commonly spotted include:

- Adult Emergence: Mid-June to early July

- Mating Window: ~2–3 weeks

- Flash Pattern: Long (~1 sec) single flash in a J-shaped upward flight every 5–6 seconds

- Female Response: Stationary on vegetation; responds ~2 seconds after male flash

- Time of Day: Dusk to early night

- Habitat: Moist meadows, open fields, forest edges, and riparian zones

- Diet:

- Larvae: Carnivorous; feeds on snails, slugs, and earthworms

- Adults: Do not feed; rely on stored energy from larval stage

- Communication: Bioluminescent courtship; species-specific flash timing and shape

- Unique Traits:

- Males fly in a “J” arc while flashing

- Females are polyandrous; may mate with multiple males over several nights

- Nuptial gifts (spermatophores) influence female mate choice

- Defense: Contains lucibufagins (bitter-tasting steroids); reflex bleeding deters predators

- Threats: Light pollution, pesticide use, habitat loss

- Adult Emergence: Late June to mid-July

- Mating Window: ~2–3 weeks

- Flash Pattern: Single yellow flash every ~5 seconds; males fly in straight lines ~1–1.5 m above ground

- Female Response: Stationary on vegetation; responds ~4–6 seconds after male flash

- Time of Day: Begins ~40 minutes after sunset; active for ~2 hours

- Habitat: Open fields, meadows, pastures, and bogs

- Diet:

- Larvae: Carnivorous; feeds on earthworms, snails, and slugs

- Adults: Do not feed; lifespan ~2 weeks

- Communication: Bioluminescent courtship; females prefer longer male flashes, which may signal larger nuptial gifts

- Unique Traits:

- Contains lucibufagins—bitter steroids that deter predators

- Closely related to Photinus indictus, a diurnal, non-flashing species

- Threats: Light pollution, habitat loss, pesticide runoff

- Adult Emergence: Late May to mid-July

- Mating Window: ~2–3 weeks

- Flash Pattern: None; adults are non-luminous

- Female Response: Uses pheromones; males detect with serrate antennae

- Time of Day: Active in daylight—late morning to early afternoon

- Habitat: Moist forests, shady open areas, and riparian zones

- Diet:

- Larvae: Carnivorous; feeds on snails, slugs, and soft-bodied invertebrates in decaying wood

- Adults: Occasionally nectarivorous; observed feeding on milkweed nectar

- Communication: Chemical courtship via pheromones; no bioluminescent signaling

- Unique Traits:

- Both sexes fly; males fly low (~1–6 ft) through forest understory

- Larvae are bioluminescent, but adults lack functional light organs

- Exudes lucibufagins (bitter steroids) from leg joints to deter predators

- Threats: Habitat loss, pesticide use, and degradation of moist environments

- Adult Emergence: Mid-June to late July

- Mating Window: ~3–4 weeks

- Flash Pattern: Variable; males emit 1–6 rapid pulses with ~2.5 sec pause between patterns

- Female Response: Mimics flash patterns of other species (e.g. Photinus ardens, Pyractomena borealis) to lure and consume males

- Time of Day: Active after sunset; peak flashing ~30–60 minutes after dusk

- Habitat: Marshes, spruce forests, moist meadows, and swampy lowlands

- Diet:

- Larvae: Carnivorous; feeds on snails, worms, and soft-bodied invertebrates

- Adults: Females prey on other fireflies; males may not feed

- Communication: Bioluminescent courtship and aggressive mimicry; flash-answer dialogue lasts ~10–20 sec before mating

- Unique Traits:

- Most abundant Photuris species in Ontario

- Sequesters lucibufagins from prey for chemical defense

- Flash behavior varies by region and individual; males increase flash count when approaching females

- Threats: Light pollution, habitat loss, and pesticide exposure

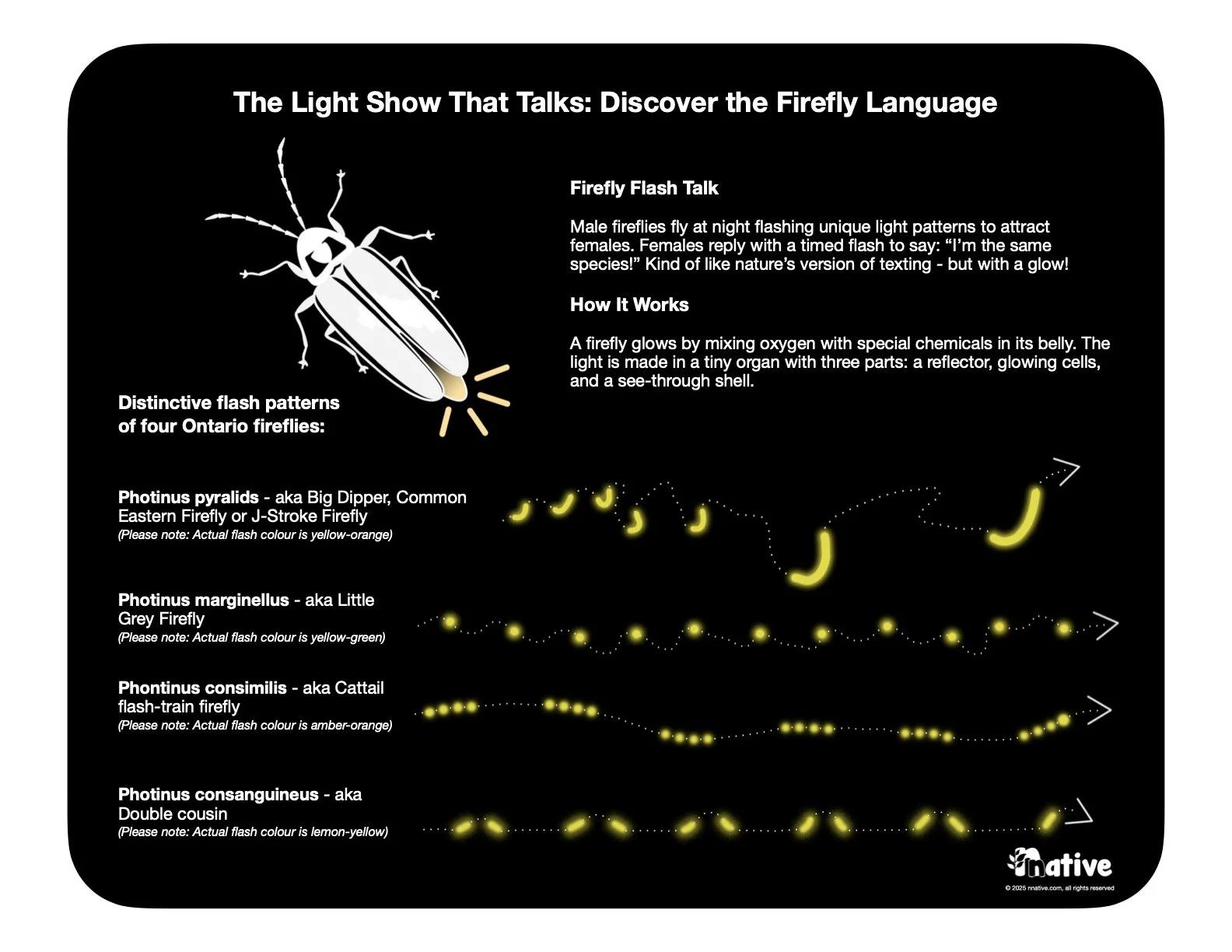

Each species has unique flash patterns, shaped by evolution to attract mates. Some flashes dip, others blink, and a few glow steadily; like a Morse code of summer love.

Life Beneath the Glow: Understanding Firefly Biology

Photinus pyralis

The “Big Dipper” firefly. Known for its J-shaped flash pattern at dusk, this adult was gently captured for daytime observation by curious young naturalists in a Hamilton backyard.

Fireflies undergo complete metamorphosis, cycling through four distinct stages: egg, larva, pupa, and adult.

Eggs are laid in moist soil or leaf litter.

Larvae hatch in two to three weeks and live for one to two years underground, preying on snails, slugs, and worms.

Pupae develop quietly in the soil.

Adults emerge for just a few glowing weeks to reproduce, often without eating at all.

The larval stage, longest and most ecologically important, deserves our focused protection. It’s during this time that fireflies contribute to pest control and serve as indicators of healthy habitats.

Step 1 – Safeguarding Fireflies: Why Timing and Habitat Matter

Long before they blink across the sky, fireflies begin life hidden in the soil and leaf litter, quietly feeding, growing, and preparing for their summer debut. Most species are active between May and August, and during this period, even small disruptions can interfere with their ability to survive and reproduce.

Photuris fairchildi

A true “femme fatale” of the firefly world. Females of this species mimic the flash signals of other fireflies to lure in unsuspecting males… then eat them. The stolen chemistry even helps them repel predators.

(Photographed during a quiet summer dusk in a Hamilton garden.)

To give fireflies the best chance at success, especially during their most delicate stages, consider these seasonal practices:

Avoid disturbing the ground. That’s including mowing, tilling, or compacting soil! Particularly near wetlands, meadows, or vegetated areas where larvae develop.

Avoid pesticides. Broad-spectrum chemicals can poison larvae and their prey, even if applied far from visible firefly activity.

Protect the dark. Fireflies communicate with light, and artificial brightness, especially at night, can disrupt mating. Use dim, warm lighting or turn off unnecessary fixtures during peak firefly season.

By syncing our actions with fireflies' life cycles, we create space for their full glow to emerge and for more magic to return to the summer night.

Step 2 – Lighting the Way: Why Firefly Habitat Starts from the Ground Up

Fireflies don’t ask for fancy landscapes; what they need is moisture, shelter, and space to grow. Wet meadows, forest edges, and untamed gardens provide the perfect mix of damp soils and protective cover where larvae can feed and mature.

The secret lies in native vegetation. Deep-rooted plants like grasses, shrubs, and wildflowers help trap moisture, stabilize soil, and sustain the insects fireflies prey on. Even small changes in your yard or local green space can nurture their entire lifecycle.

Here’s how to make it happen:

Plant native species adapted to your region’s climate and soils. For example in rain gardens, low-lying areas, or naturally moist soils in Ontario, consider wildflowers like Cardinal Flower and Joe-Pye Weed, or prairie grasses such as Indian Grass and Switchgrass. These moisture-loving plants add structure, shelter, and support the insect food web that fireflies depend on.

Leave the leaf litter. Firefly eggs and larvae rely on it as insulation and hunting ground.

Keep riparian zones wild. Don’t mow or disturb areas near creeks and wetlands—these are prime breeding sites.

Skip thick mulch. Wood chips can block rainfall and prevent egg-laying.

In short, a slightly “messier” garden is a kinder place for fireflies. Diversity below the knees brings sparkle to the skies.

Each Ontario firefly species has its own signature flash pattern, a coded dance of light that enables courtship and connection. Disruption by artificial lighting can blur these messages and break their communication.

Step 3 – When Darkness Matters: Why Light Pollution Threatens Firefly Romance

For fireflies, summer nights are meant for conversation, flashes exchanged like whispers in the dark. But as our evenings grow brighter, these glowing courtship signals are being washed away by artificial light.

Fireflies rely on darkness to find love. Each species has a unique flash pattern: a flicker here, a pulse there, messages shared between airborne males and grounded females. But modern lighting, especially white and blue-toned LEDs, overpowers their glow, preventing them from locating mates.

Thankfully, small changes can make a big impact:

Use warm-coloured bulbs like amber, yellow, or red LEDs. These are less disruptive to fireflies and friendlier to other nocturnal wildlife.

Turn off unnecessary lights, indoors and outdoors, especially during peak firefly months.

Install motion sensors and timers so lights only activate when needed.

Shield outdoor fixtures downward to minimize skyglow and glare.

Draw curtains at night to keep indoor light from spilling outside.

Creating even just a pocket of true darkness in your backyard or community green space gives fireflies a chance to reconnect. After all, when we dim the lights, we invite a little more magic back into the night.

Step 4 – Silent Killers: How Pesticides Threaten Firefly Survival

That quiet flash at dusk might seem timeless, but its journey began in the soil, where firefly larvae hunt for soft-bodied prey. Pesticides, especially broad-spectrum insecticides like neonicotinoids and organophosphates, threaten that cycle by wiping out their food and contaminating critical habitat.

Even when fireflies aren’t sprayed directly, runoff can infiltrate the moist soils they rely on, impacting eggs, larvae, and their prey long after application.

Here’s how to protect their fragile underground world:

Avoid insecticides from May through August, when fireflies are active.

Check product labels, especially for lawn or grub treatments.

Keep chemicals away from creeks and wetlands, which double as breeding grounds.

Use targeted, low-toxicity options only when absolutely necessary.

Preserving fireflies doesn’t require drastic change, just thoughtful choices that keep the soil alive and glowing.

Step 5 – A Landscape Alive with Light: Why Every Backyard Matters

At first glance, fireflies may feel like a luxury of summer, an enchanting but optional part of the ecosystem. In truth, their steady disappearance is a warning: we’re dimming not just their light, but the health of the environments we share.

The good news? Restoring firefly habitat doesn’t require sweeping reforms. It begins right outside your door.

Rethink the lawn. Skip the sprays, let the grass grow, and allow your yard to host a little more wildness.

Re-wild with intention. Plant native species, leave the leaves where they fall, and keep moisture in the soil.

Protect the dark. Reduce outdoor lighting and invite twilight back into your landscape.

Even small changes, like pausing a mowing routine or skipping a pesticide treatment, can ripple out into something bigger: a garden full of glimmers, a neighbourhood alive with song and spark.

When we allow the land to breathe, fireflies answer with light.

In the end, protecting fireflies isn’t just about saving a single species, it’s about safeguarding the quiet rituals that connect us to nature. Their gentle flashes remind us that even small lives carry beauty, purpose, and power. When we tend our landscapes with care, we don’t just make room for fireflies, we make space for awe. Let’s keep the nights dark, the habitats wild, and the summer skies alive with light.